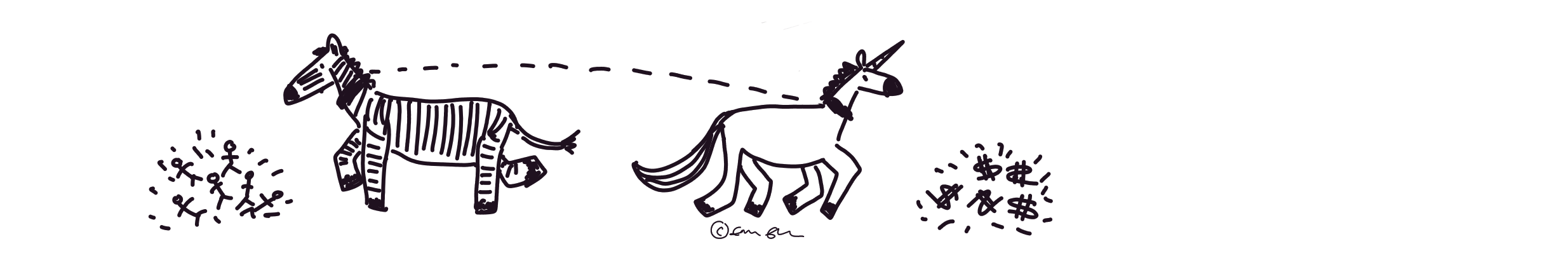

It is standard business development practice to say we need more ‘unicorns’ – a privately held start-up company valued at over $1 billion (not to be confused with the mythical unicorn). The energy, money and success (sometimes) associated with these firms is attractive. However, the coining of the term has recently been contrasted with the less mythical, and rather better-known zebra – animals adapted to challenging savanna habitats. We all know the stories, but, impressive though they are, not all organisations need a unicorn approach.

Jennifer Brandel, Aniyia Williams, Astrid Scholz and Mara Zepeda started the ‘Zebras Unite’ movement in 2015, creating a manifesto that outlines an alternative to the current technology and venture capital structure:

“It rewards quantity over quality, consumption over creation, quick exits over sustainable growth, and shareholder profit over shared prosperity. It chases after “unicorn” companies bent on “disruption” rather than supporting businesses that repair, cultivate, and connect.” (Read the Manifesto here)

The Zebra manifesto identifies quite a different kind of company, one which is both profitable and improves society, mutualistic (banding together to protect and preserve one another, boosting collective output), and uses words like inclusive, regenerative, community oriented, and cooperative.

The Zebra Manifesto authors go on to say:

“We believe that developing alternative business models to the startup status quo has become a central moral challenge of our time. These alternative models will balance profit and purpose, champion democracy, and put a premium on sharing power and resources. Companies that create a more just and responsible society will hear, help, and heal the customers and communities they serve.” (Zebra Manifesto)

What does this mean for companies and organisations (both for- and non-profit)? It comes down to the attitude and mindset inherent in the company, and the effect that has on workplace culture. Unicorns are only useful if they fit the attitude and mindset inherent in the company, and the effect that has on workplace culture. If not unicorns, then what?

As an example, in 2015 I co-founded a non-profit organisation, Capacity, dedicated to supporting human potential. We didn’t think of it in those terms at the time. I joined a group of concerned social workers, psychiatrists, doctors, NGO volunteers and employees who work with refugees, who came together to address the issue of long-term refugee unemployment.

Once launched, we started attracting some attention, people wanted to meet ‘the founder’, find out what motivated them, understand their vision. This was great, but we had an issue. The person who first initiated the discussion had already moved on, and the official ‘founders’, those present at the moment the association was formally founded, were no longer involved. As the only person who had been present at some of the early discussions and at the official ‘founding’ meeting, I was often described as ‘the founder’. Yet, I did not regard myself as ‘the’ founder for several reasons: it was not my idea, rather an initiative built by over 30 people working together over a year, with those of us who had the luxury of time being the ones taking it forward. It has grown into an organisation driven by a mission to serve a community that has few opportunities.

The focus of the organisation and its supporters has to be on our community, their issues, challenges, hurdles and successes. The very idea of ‘The Founder’ runs counter to the organisation’s ethos and way of working.

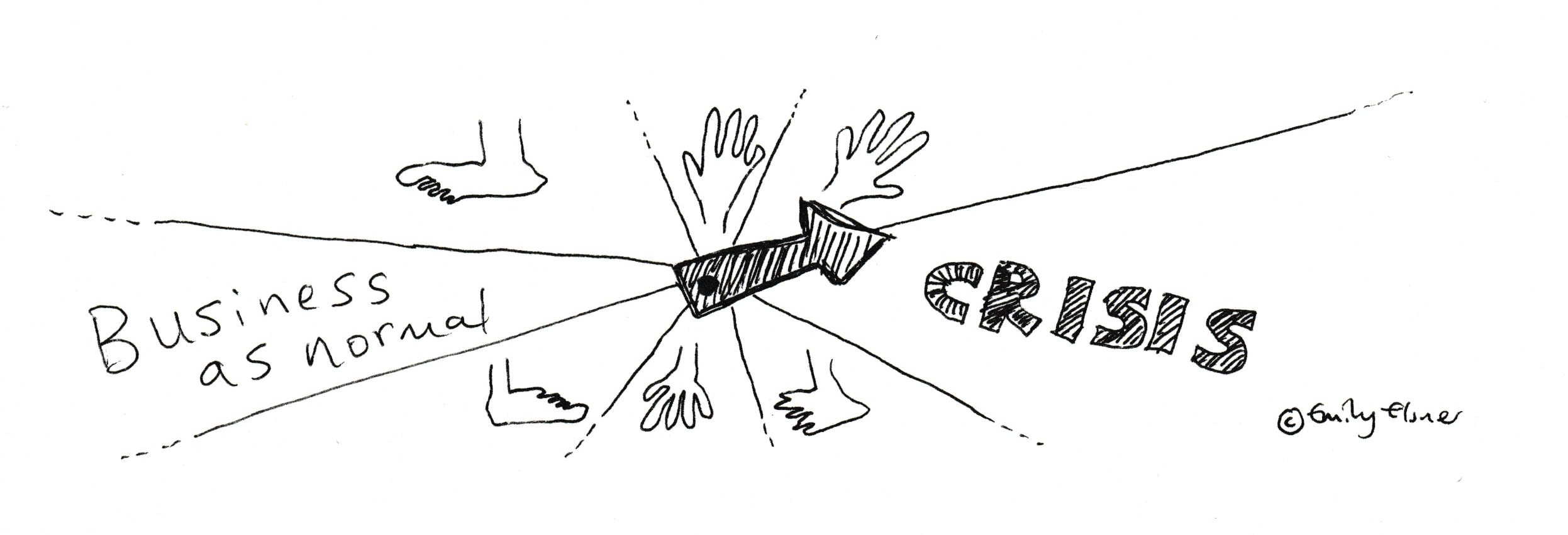

This sat at odds with our use of start-up language, and the implication that this brings of a ‘heropreneur’ fighting against the odds to bring to life a company or organisation. Heropreneurs are often associated with unicorns – how else can a company grow aggressively and rapidly (also known as blitzscaling), unless there is someone in charge of strategy who is willing to take on risk and bring funders along for what is likely to be a rapid ride to success or failure?

In the case of Capacity, the media wanted to interview the founder, the founder was invited to events, we even had a newspaper refuse to speak to the team-member trained in media relations, because they were not ‘the founder’, yet our ethos as a team saw all of us as equally responsible for the success of our beneficiaries, our participants.

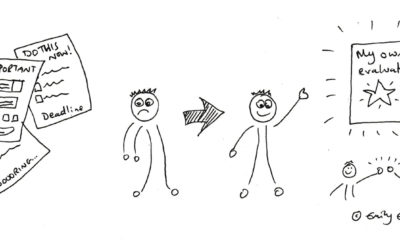

Valentina, one team member saw a solution: to redefine the concept of ‘founder’ to acknowledge the incredible contributions made by team-mates who simply happened to join later in the process. Our community now has 6 (soon to be 7) co-founders – defined loosely as people involved for more than 1 year, and who have made outstanding contributions to the organisation’s activities, direction, and success. Each year, the organisation discusses who they would like to invite to adopt this title, to ensure that all contributions are given a chance to be considered.

Without realising it, we were reacting to the dominant unicorn-heropreneur mindset: focusing away from egos and unique, charismatic leaders and towards building a more cooperative, sustainable organisation dedicated to public service. We took a zebra approach to leadership and organisational management. As a non-profit, this is of course a little easier than for for-profit organisations, but leadership style matters to everyone in an organisation, no matter what it does.

Zebra companies give space to focus on internal impacts of the companies – on the staff who work there, and through them on the communities and customers that they serve and live in. This is especially important given entrepreneurship’s history on mental health (see here and here) and the emerging effects of long-term working from home on stress/burnout. It also reflects a trend within the investment and foundation space, where grant-makers and impact investors realise that they have a role in both sponsoring organisations but also supporting the people who do the work in delivering outcomes for society and customers.

Our organisation, as well as having redefined ‘co-founding’ to be more inclusive and to recognise the great contributions of team members, has also always had an exceptionally supportive and open approach to issues. Focused on serving a community faced with many challenges both personal and systemic, the team has found that an open discussion of personal and organisational issues internally and with our beneficiaries builds trust rapidly, and ensures that team members facing difficult moments can deal with those safely and effectively. We are proud to take a zebra approach to our decision-making and management.

Organisations don’t become zebras (or camels) overnight. How do you gain the benefits of the zebra approach to organisational leadership? Any organisation can consider its internal culture and how it provides support and nurtures staff members to achieve fully. By thinking about where you want to go, setting sensible impact targets and then evaluating progress towards them, any organisation can move towards becoming more zebroid and less mythical…

Targets that empower the inner organisational zebra may not be in the standard impact playbook, but they can be developed. Ask me if you are interested.